Over two weeks in the Caucasus, I lost track of the number of churches I set foot in after twenty-five or so. Most of my visits were brief, just a quick peek inside to see the artwork and observe the local people making their rounds to pray before each icon. A trip to the Caucasus will inevitably lead you through countless churches and monasteries. But come Sunday, it was a Catholic church that I was looking for.

To my surprise, my search was easiest in predominantly Muslim Baku. Despite a rather long walk to St. Mary’s, I found a diverse congregation celebrating mass in English in a small but packed church. Baku is an oil city, so many of those people are likely expats.

Then I was off to Georgia, where there likely would be no such expat community.

In Georgia, two saints are the namesake for over ten percent of the population. The obvious is Saint George, who was martyred in modern-day Turkey in the year 303 AD. Both England and Georgia consider Saint George as their patron and have adopted his red cross on their flags, but the latter went a step further, naming the country itself after him (in most languages except Georgian itself – presumably Georgia is easier for foreigners to pronounce than Saqartvelo). The familiar image of Saint George on horseback and slaying a dragon is a recurring theme in Georgian churches and public monuments.

The other is Saint Nino, a fourth-century missionary in Georgia. She is credited with inspiring the Georgian king to convert to Christianity in 319 AD, an event which made Georgia the second nation in the world officially to embrace the new religion. Naturally, Saint Nino features prominently on the frescoed walls of Georgian churches. She is easily identified carrying her own distinctive droopy-armed cross. In a land of winemakers, Nino assembled her cross with a local – if not very rigid – material: grapevines.

Most Georgians belong to the Georgian Orthodox Church, one of many Eastern Orthodox churches that separated from the Roman Catholic Church in the Schism of 1054. As all Eastern Orthodox churches are in communion with each other, the Georgians naturally share religious ties with the Russians and the Greeks, and the similarities are apparent in the layout of the churches and the rich iconography inside. The Georgian patriarch historically had his seat in the former capital, a town twenty minutes outside Tbilisi called Mtskheta (it’s not a typo, Georgians just don’t care much for vowels).

Mtskheta is a sleepy, low-slung town at the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi rivers, a far cry from the busy streets of Tbilisi. I visited on a rather dreary evening and wandered around, popping in and out of the various UNESCO-listed churches. Souvenir stalls aimed at tourists and pilgrims alike line the quiet streets, and down by the riverfront, decrepit motorboats sit by the docks beside signs advertising sightseeing rides. By far the biggest thing in town – both physically and in terms of importance – is Svetitskhoveli Cathedral. It’s built with the same form as other Georgian churches, but on a much larger scale and was filled to capacity with wedding-goers when I tried to squeeze in. Despite its impressive architecture, Mtskheta has a somewhat neglected feel. The Georgian Church is now run from a shiny new cathedral in Tbilisi.

At the end of my week in Georgia, I was again looking for a Catholic church, and my search was again pretty straightforward. There are two Catholic churches offering several masses throughout the day in a variety of languages. I chose the morning English mass at Saints Peter and Paul. This church was more historic than St. Mary’s in Baku, but the pews were sparsely occupied. The Georgian Orthodox Church plays a huge role in all aspects of society and other denominations are likewise regarded warily. Also the sound system in the church was hopeless, so the mass may as well have been in Georgian.

I continued my trip south to Armenia, another ancient Christian nation. In 301 AD and after twelve years of imprisonment in a dark dungeon, St. Gregory the Illuminator illuminated Christianity for the Armenian king and earned his place as the country’s patron.

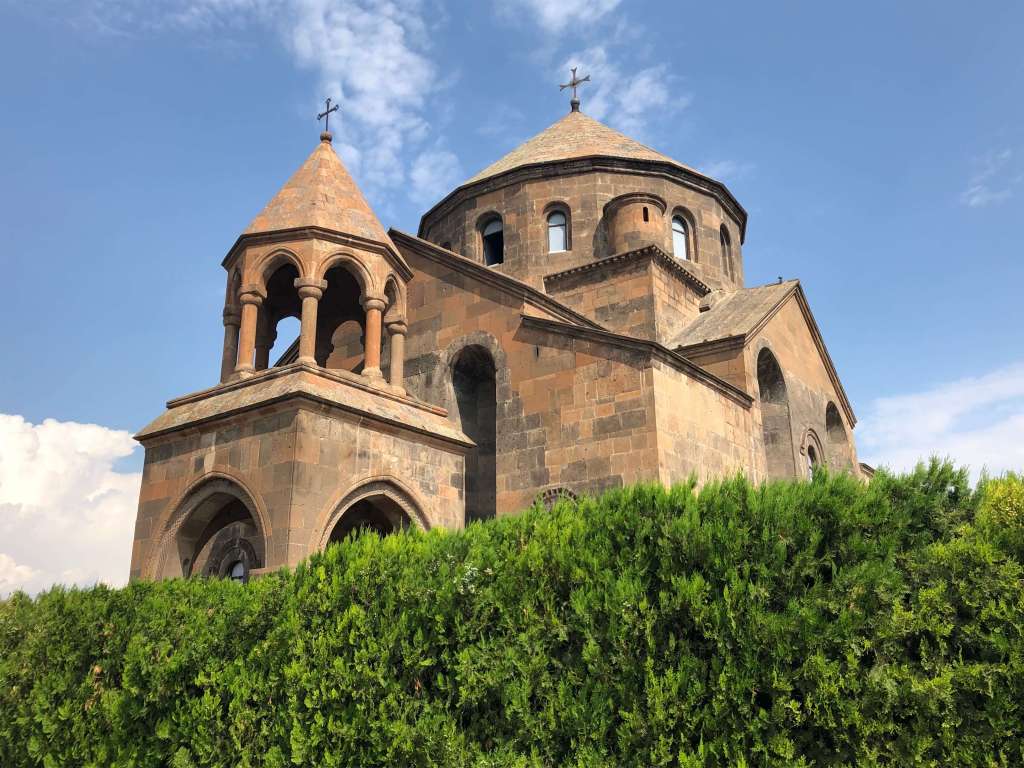

Judging by the visual similarity of Armenian and Georgian churches, you’d be forgiven for thinking they are the same. The biggest differences I noticed were the occasional bell tower on Armenian churches, and the tendency of Armenian churches to have flat-sided rather than round domes. But the two are not interchangeable.

The Armenian Apostolic Church, to which most Armenians belong, is actually part of a relatively obscure branch of Christianity. It’s called Oriental Orthodoxy, and though you might assume that’s the same as Eastern Orthodoxy, it’s not. The Oriental Orthodox churches parted ways with the Catholic Church in 451 AD, six centuries before the schism that created Eastern Orthodoxy. Interestingly though, despite such a long separation, the Oriental Orthodox churches and the Catholic Church actually agree on quite a lot. The major theological difference was largely a misunderstanding resulting from language and culture barriers between Rome and frontier Asian lands like Armenia.

The leader of the Armenian Apostolic Church has his seat just west of Yerevan in the ancient city of Vagharshapat, also known as the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. Like its Georgian counterpart, Etchmiadzin is a breath of fresh air compared to the capital, though it’s somewhat more quirkier than Mtskheta. In the space of a five minute stroll down the main street, I passed a family huddling under a ten-foot-tall metal umbrella (presumably a bus stop), witnessed two rather comical vehicular mishaps, stopped to admire a street artist at work on a wooden coffee shack, took a photo of the “I ❤️ Etchmiadzin” sign, and photobombed a wedding party (I’m telling you, they’re unavoidable in the Caucasus).

Aside from several historic churches, Etchmiadzin is home to a seminary, a beautiful library, and the oldest cathedral in the world. The rather modest stone cathedral is currently under renovation – the latest in a long history of renovations and reconstructions – but it nevertheless draws groups of pilgrims and tourists. After I’d seen the sights, I passed the afternoon on an outdoor terrace in this Oriental Vatican enjoying a meal of cilantro-tomato-cucumber salad, Sevan trout in pomegranate sauce, and a glass of Areni wine – it doesn’t get more Armenian than that!

The last day of my trip arrived, and it was Sunday again – the most challenging yet. My go-to method of typing “Catholic church” into GoogleMaps led me down a rabbit hole of confusing terminology. The Cathedral of Saint Gregory the Illuminator looked promising, as did the numerous other saint-somethings that popped up in the search results. A little investigation into each one led me to the website of the Catholicosate. Aha, that must be what I’m looking for, right?! Except that “catholicos” is not actually a term I’ve ever heard used in the Catholic Church. These were actually Armenian Apostolic churches, and there seemed to be no Roman Catholic church in the entire country.

One by one, I crossed off almost every church from the list, until finally I was down to one option, a nondescript marking on the fringe of Yerevan labeled “Armenian Catholic Church.” The web link took me to the homepage of the Patriarchate of Cilicia, seated at a Cathedral of Saint Gregory the Illuminator – a different one, in Beirut, Lebanon.

So it’s a patriarchate, I thought, that’s Orthodox too, right? And yet, there was Pope Francis, smiling from the homepage, which could only mean one thing. The Armenian Catholic Church, it turns out, is a branch of the Armenian Apostolic Church that reunited with the Catholic Church in the eighteenth century but kept its traditional Armenian liturgies and rituals.

Address in hand, the battle was only half won. Showing up at the right time was the next challenge, and given my inability to read the Armenian script and Google’s inability to decipher the website’s font, this was a bigger hurdle than anticipated. My research led to dead end after dead end – oh well, at least I’d tried. But then by chance, I came across an email address written beside a physical Yerevan address. Worth a try, I thought. The response was surprising quick, albeit brief: mass at 11:00.

At 10:45, a taxi dropped me off on a side street behind a store shaped like a giant champagne bottle and surrounded by apartment towers. Standing in the middle of the street, as confused as me, was another tourist. He asked me first if I spoke English, then if I knew where the church was. Neither of us had a clue. We walked up and down the street and finally entered the only doorway that appeared not to be a residence. A man stood in the foyer, observing us curiously. “Catholic church?” we asked. “Only one in Yerevan,” he responded, gesturing toward a portrait of Pope Francis as he opened the back door for us, “around and to the right.”

The church a small room with a low ceiling on the first floor of one of the apartment towers. Perhaps one hundred people filled the short rows of pews until there was standing room only. A strong choir in the back filled the air with energy, and the congregation participated fervently. Occasionally someone would get up and adjust a window to redirect the airflow in the hopes of catching a breeze. Up front the priest and deacon crowded the small sanctuary in a cloud of incense and chanting. Five altar servers hurried around doing a myriad of jobs including rattling a staff lined with tiny bells for minutes on end and occasionally drawing a heavy curtain theatrically across the altar.

No doubt the Armenian rite is very foreign to those accustomed to the Latin rite, but of course a Catholic mass should not be entirely unrecognizable. I followed along as best I could despite the language barrier and the long-winded prayers. Nearly two hours later the Catholics of Yerevan dispersed, and I hailed down an inbound marshrutka, exhausted from the stress of incomprehension, but grateful to have experienced something so simultaneously foreign and familiar.

In some places I’ve traveled, the only way I’ve been able to find a schedule for Sunday Mass is to show up at the church on Saturday and hope there’s a sign posted near the door. Although I’m not sure that would have worked for a church inside an apartment complex.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha yea it was definitely in an obscure location, probably with no expectation of non-locals trying to show up!

LikeLiked by 1 person